The Present Time Challenges

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.33637/2595-847x.2021-118Keywords:

EditorialAbstract

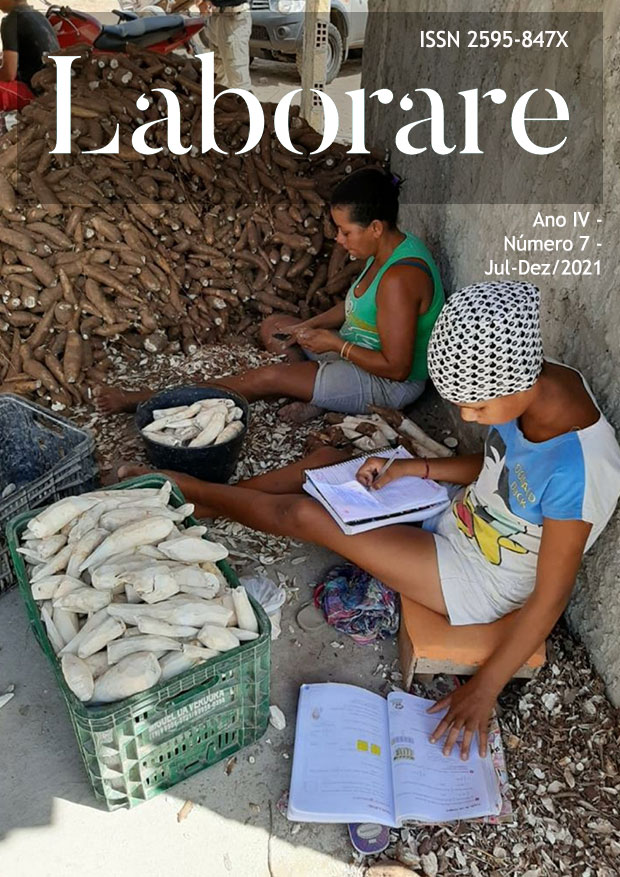

The issue of Laborare journal that we are presenting reflects the seriousness of the moment we are facing. A moment of crisis about what the State should represent and how its institutions should act. The Labor Law is at the center of this crisis, as it regulates the founding social relationship, the one that allows or prevents physical survival. It is through paid work that in a society such as ours, the money needed to buy food, clothing and live is obtained. So, those who do not have a job are not, in the end, able to survive. The recognition of this reality, as well as the tension caused by the workers' movements and the very need of the system for there to be consumption, has demanded over the years the construction of social protection webs. Labor Law proved to be the limit of possible exploitation, as an article published in this issue, clearly demonstrates.

Our model of social organization is based on private property and on the assimilation of everything, including people (labor force) and natural resources, to the condition of merchandise to be traded. Without the conviction that we own the workforce, perhaps we would revolt with the fact that access to food, clothing, medicine, or housing is, as a rule, only given through the money obtained by exchanging work for wages. A wage that only exists if private property (labor force) is traded on the market. It is precisely the Labor Law that reveals, more clearly, that what appears as the exercise of the freedom to work is mandatory work, as far as it constitutes a condition for physical survival. Therefore, is so concerning the entire movement that for decades has been trying to deflate the concept of employment bond, which in this journal is analyzed with in the article that deals with the uberization of work.

What we are experiencing today is not just the crisis of this historical understanding of the need to impose limits on the exchange between capital and labor. It is the imposition of a new order, in which child labor, violence against women and other issues, which we thought had been overcome, are once again defended by people who hold public positions. That is why the discussion in the articles about the repercussions of the pandemic on the learning contract and on women's work is so important. Old themes are so persistently present in a country that has reached the tragic figure of 14.8 million unemployed. According to data for the first quarter of 2021, released by the IBGE, there are already 86.7 million informal workers. People who exchange work for salary, but do not have a recognized relationship, do not enjoy vacations, cannot get sick, because if they do not work, they receive nothing, although the monthly bills, with which they guarantee food and shelter, keep arriving.

The issues raised in the articles gathered here are, in fact, wounds never dealt with by a history of disrespect for the most elementary rights of those who make a living from work. And they gain a painful depth from the moment when, in view of the 2008 crisis and without knowing how to deal with the social reaction of 2013, a process of weakening the commitment to the 1988 constitutional order begins, which has the point of symbolic reference the coup that removed the first woman elected President of the Republic from power. Breaking with respect for the liberal right to vote, removing exactly a woman from post, under a discourse that focuses exclusively on a workers' party and, therefore, also on the metalworker who previously held the presidency, is a caricature of what we are: a founded country under the patriarchal, authoritarian, and racist logic.

In such a society, enforcing social rights is a great challenge. Therefore, in the little more than thirty years that separate us from the 1988 Constitution, we have never been able, not even under the government of a workers' party, to effectively enforce the right to protection against dismissal, the right to an adequate distribution of income and land, the right to decent employment. The precarious formulas that are identified today from the neologism of uberization have always been present.

There is no doubt, however, that disrespect deepens when the official discourse is completely disconnected from the pact signed in 1988. This is the depth of the crisis we face today, and which is well represented by the legislation that has been enacted during the pandemic, whose content is precarious increasingly, it disfigures the Labor Law more and more, including regarding the destruction of health and safety standards at work. In addition to such legislation, there is jurisprudence contrary to social protection. The discussion that takes place in the article that deals with the uberization of work helps us to understand the social drama that is barely hidden in these political options to increasingly abandon the Brazilian people.

It is true that this is not a movement that is limited to the Brazilian reality, nor can it be faced without a deep reflection and review, including our legal training. To help indicate possible paths for the tension and change that are urgently needed in this context, we also have in this issue an article that deals with the importance of a critical study of Labor Law, based on university extension experiences.

A reading experience that will keep us steadfast in the hope of overcoming this dark phase of our recent history. Other challenges, perhaps even more tragic, have already been faced by the working class and those dealing with Labor Law in Brazil. Reading and reflecting on the legal issues gathered here is, without a doubt, a healthy way of acting politically, in the broadest and most positive sense that this word can reach.

Enjoyable reading!

The editors

Downloads

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.